History and situation in Poland

The birth of Poland symbolically dates to 966 and the Baptism of Poland, when Duke Mieszko I adopted Christianity as the official religion of the new state. The 16th century marked the so-called “Golden Age of the Republic,” the dynamic development of humanism, literature, architecture, and art from the Renaissance, as well as the Reformation period. It was a time of a tolerant and multicultural society, during which Poland developed legal solutions that were innovative on a European and worldwide scale, fostering peaceful coexistence and even cooperation between different faiths (1570 and 1573).

In the late 18th century (1791), Poland was the first in Europe and the second in the world (after the United States of America) to adopt a written constitution. Between 1772 and 1795, as a result of the three partitions (gradual division of the Polish territory between Russia, Prussia, and Austria), the country disappeared from the world map for 123 years.

It was only at the end of the First World War (1914–1918) that Polish statehood was reborn: the independent Second Republic was established on 11 November 1918. However, in 1939, the Second World War broke out. Massive war crimes were committed during the German occupation of Poland, including the systematic extermination of the Jewish population, resulting in the extermination of some 6 million Jews from all over Europe, including around 3 million Polish Jews. The Soviets too committed numerous crimes, including mass deportations of populations of various groups to Siberia and executions of Polish prisoners of war and civilians. Despite the dangers, Poles engaged in conspiratorial activities and fought against the occupying forces.

When the war ended in 1945, Poland’s borders were pushed westward and the country was incorporated into the Soviet sphere of influence. This started the period of belonging to the so-called communist bloc. The reconstruction of the country began, but the overall enthusiasm was marred by state seizures of property rights to land, businesses and capital, and an ideologization of social relations. Freedom of speech and freedom of assembly were curtailed, and the communist authorities censored the media and restricted press freedom. They also launched a widespread campaign of repression against political opposition, trade union activists, intellectuals, artists, and the clergy. In the 1950s and 1960s there were protests against the authorities, and the 1970 workers’ protests were suppressed by the government’s armed forces. It was out of this period that “Solidarność” was born, a movement that united different social groups and worked for political and economic freedom. The communists tried to contain this mass social movement by imposing martial law on 13 December 1981. Social tensions and a collapse of the economy led to talks between the authorities and opposition. The “Round Table” talks in 1989, resulted in an agreement to partially free elections, a huge success for the opposition. The communists were thus peacefully removed from power and a new period in Polish history began.

The events unfolding in Poland triggered changes in other communist countries, with the subsequent fall of the Berlin Wall (1989) and the collapse of the Soviet Union (1991). The Roman Catholic Church, perceived in society as a refuge for the then opposition circles, was granted official privileges in its relations with the state, and it gained influence on the new reality that was taking shape in Poland. At the same time, a period of dynamic capitalist development began. In 1999, Poland joined the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) and on 1 May 2004 it was admitted to the European Union (EU).

The political order of the Republic of Poland was set out in the constitution of April 1997, which defined the country as a parliamentary republic based on pluralism, the rule of law, and respect for civil society. The constitution states that Poland is a “democratic state ruled by law and implementing the principles of social justice,” with a tripartite division of power. The legislative power is exercised by the Sejm, the highest decision-making body, and the Senate; the executive power by the Council of Ministers and the President; and the judicial power by the courts and tribunals.

The accession to Western structures accelerated the modernization of Polish society, causing a flare-up of ideological and political disputes that led to its polarization. Under the banner of extensive reforms, the right-wing Law and Justice (PiS) party came to power in 2015. Its judicial reforms raised controversies and were contested by parts of Polish society and criticized by EU institutions. There were also public protests about reforms in education, which denounced the attempts at subordinating education to one particular worldview. The refugee crisis on the border with Belarus, which deliberately opened up its territory to refugees from African and Middle Eastern countries wishing to enter the EU, reverberates loudly in Poland and beyond.

In 2020, the COVID-19 pandemic reached Poland, resulting in restrictions and lockdowns as well as financial distress for many individuals and businesses. A year later, a free vaccination program for all citizens was introduced. The following year, 2022, saw rising inflation that affected the financial situation of Poles and led to economic hardship.

On 24 February 2022, Russia launched an armed invasion of Poland’s neighbor, Ukraine. Poland provided shelter for millions of refugees and supported their integration into Polish society. Many Polish women and men organized collections and aid campaigns for Ukraine, and publicly demonstrated their support for Ukraine’s sovereignty and territorial integrity. Poland sent to Ukraine humanitarian aid such as food and medicine convoys, and provided support in military training and equipment. Actively supporting Ukraine, it also joined the efforts of the international community for peace in Ukraine and the strengthening of Ukraine’s position in the region and in the world.

High inflation has become a real concern for Polish families. The significant rise in prices in recent months has left many families feeling financially insecure. There is an ongoing crisis in health care, which is due, among other things, to lack of adequate funding and insufficient numbers of health care professionals. Aware of the challenges, Polish society engages in many positive campaigns and valuable initiatives. One of these is the annual fundraising campaign of the Wielka Orkiestra Świątecznej Pomocy (Great Orchestra of Christmas Charity), a foundation which for 31 years has organized collections for much-needed medical equipment that is then purchased and donated to hospitals. In 2022, it raised a record-breaking amount of PLN 224,376,706 (or around EUR 52,181,000). Funds that will be raised in 2023 will go toward diagnostic equipment related to the early detection of sepsis.

In 2023, Poland will hold its next parliamentary elections, and local government elections are scheduled for 2024.

History of Lutheranism in Poland

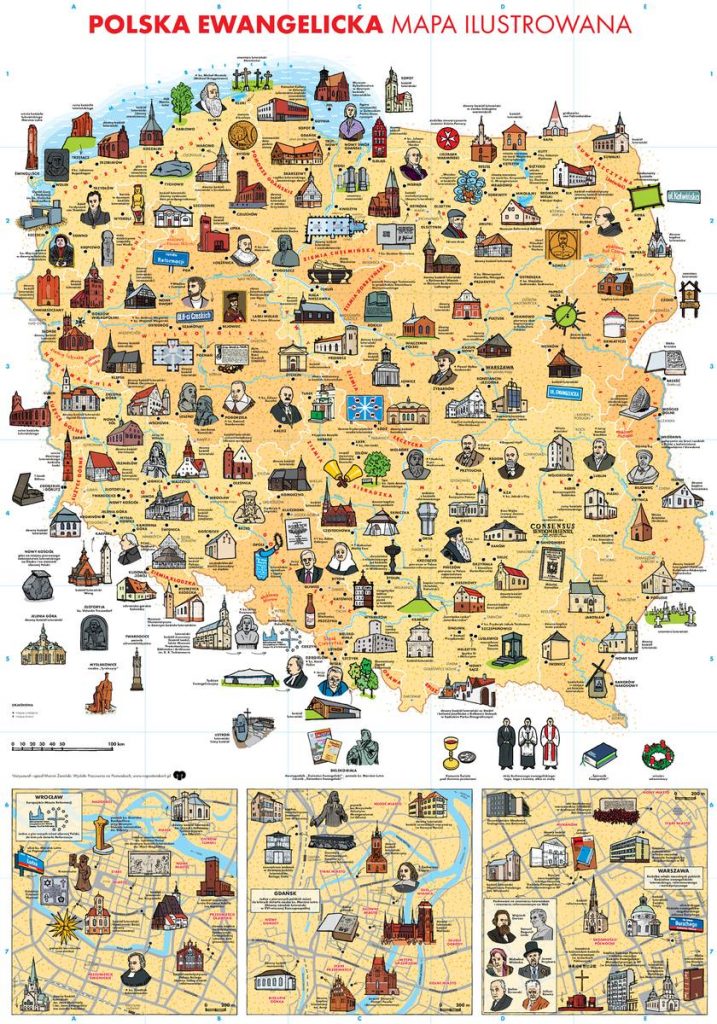

In the 16th century, Poland entered the period of its greatest prosperity known as the “Golden Age.” It was ruled by kings of the Jagiellonian dynasty, but the role of the nobility and the magnates was becoming increasingly important. Poland succeeded in a long war against the Teutonic Order (a Catholic religious institution founded as a military society); its monastic state was transformed into the secular principality of Prussia, which had been dependent on Poland. Its ruler, Prince Albrecht Hohenzollern, embraced Lutheranism, and Prussia became the first all-Lutheran state in Europe in 1525.

The two main currents of the Reformation reached Poland as early as during the reign of King Sigismund the Old (1467–1548). The northern part of the republic was inspired by the writings of Martin Luther and the influence of Lutheran Königsberg, while the southern part – through contacts with Silesia – mainly by impulses from Switzerland and Germany. The Reformation in Poland reached its full bloom in the early second half of the 16th century. The ideas of Martin Luther first reached Cieszyn Silesia during the reign of Casimir II (1449–1529). The Reformation was officially embraced by Wenceslaus III Adam of Cieszyn. Following the principle “cuius regio, eius religio” (whose realm, their religion), Lutheranism became the dominant religion in the Duchy of Cieszyn.

In the early 1550s, the first Calvinist synods began to be held in Małopolska (Lesser Poland), while the first Lutheran synod was convened in Poznań in 1555. Philip Melanchthon and John Calvin corresponded with their Polish followers, sending them specific instructions. It was at this time that the first Polish- and German-speaking Lutheran congregations appeared in Wielkopolska (Greater Poland); synods were convened regularly, and a superintendent was appointed to oversee the whole church. A key role in the development of the Polish Reformation was played by the most eminent Polish Reformer, Jan Łaski, who sought to unite Polish Protestants and establish a national church.

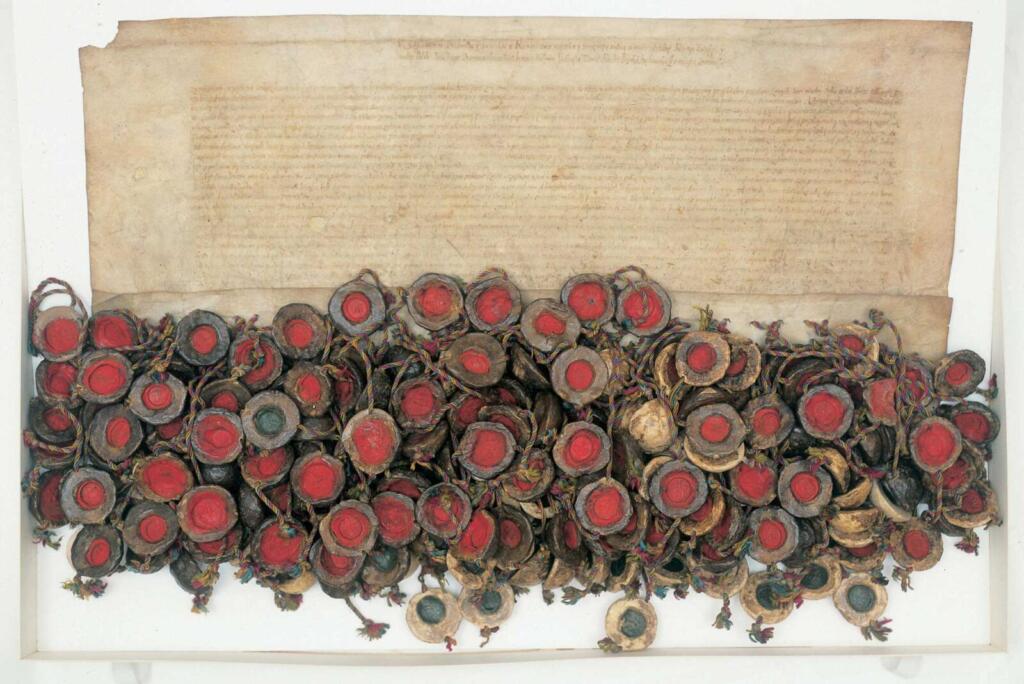

The proponents of unification succeeded in bringing about a settlement between representatives of the various Reformation denominations in Sandomierz in 1570. In the spirit of ecumenism, mutual recognition of the sacraments and the preaching ministry was declared. In addition, at the 1573 Sejm in Warsaw, the nobility passed a resolution known as the Warsaw Confederation, which guaranteed peace between those “in disagreement about the faith.” Even though the Warsaw Confederation was never implemented and failed to prevent later acts of religious intolerance in Poland, it nevertheless represented an unprecedented act of guaranteeing religious freedoms on a European scale.

Times of Counter-Reformation and Oppression

After the death of King Sigismund Augustus in 1572, the situation of Protestants in the republic began to gradually deteriorate. From the late 16th century, Polish Protestants were fated to be a religious minority in the increasingly intolerant environment of the Catholic majority. The Protestant nobility were gradually excluded from holding higher state offices. In the early 17th century, the situation also worsened for Protestants living in Silesia, then part of the Kingdom of Bohemia, where the Catholic Habsburgs were in power.

The end of the Thirty Years’ War in 1648 marked a certain relaxation of the emperor’s religious policy for Lower Silesia, which was reflected in his agreement to build three churches (called Churches of Peace) in Świdnica, Jawor and Głogów. However, at the same time in Cieszyn Silesia, events unfolded that heralded a period of the most severe religious persecution. The Habsburgs, who had ruled the duchy since 1653, deprived the Protestants of all churches. Despite the persecution, local Lutherans began to gather in the Beskid forests for secret church services in the so-called “forest churches.”

The situation was somewhat alleviated due to pressure from Lutheran Sweden in 1707, resulting in the construction of six churches (called Churches of Grace) in Silesia. One of these was built in Cieszyn, becoming the only house of prayer for Upper Silesia Lutherans for decades to come.

When Poland Disappeared from Europe’s Map

Toward the end of the 18th century, the counter-Reformation in Poland took a certain downturn. This was due, among other things, to a shift in the international balance of power, namely, the gradually increasing influence of Protestant Prussia and Orthodox Russia on politics in Poland.

Soon these countries, together with Austria, partitioned Poland, which disappeared from the maps of Europe for more than 120 years. From the end of the 18th century, an intensive process of German colonization took place in the Prussian partitioned territories. This entailed an increase in the number of Lutherans in Wielkopolska (Greater Poland).

There was a similar development in Silesia, where new Protestant parishes were rapidly emerging due to increasing industrialization. In addition to churches, educational institutions were also founded. In 1890, on the initiative of Eva von Tiele-Winckler, known as Mother Eva, the Friedenshort (Abode of Peace) care facility was established in Miechowice. It became the largest Protestant center of diakonia in Upper Silesia at the time, and was also active in the missionary field. Similar care facilities were created in 1923, which include the Eben-Ezer Care Home in Dzięgielów near Cieszyn, in Cieszyn Silesia by the Rev. Karol Kulisz.

Wartime in the 20th Century

When the First World War ended and Poland regained its independence in 1918, a difficult process began: church structures had to be rebuilt on the territory of the former partitions. Leaders of the Evangelical Church of the Augsburg Confession [Lutheran church] initiated efforts to unify the church system in the country. This was accomplished by way of the 1936 presidential decree, which introduced in the church the synodal-consistory system and the supreme office of the Bishop of the Church (leading bishop). The Rev. Juliusz Bursche was appointed to this office.

The outbreak of the Second World War opened the most difficult period in the entire history of the Lutheran church in Poland. Many pastors, not only of Polish nationality, were arrested, persecuted, imprisoned in concentration camps, and many lost their lives. The occupiers confiscated the property of Polish parishes.

Post-War Reconstruction

The post-war years marked a slow and arduous period of rebuilding church structures. In the political reality of an Eastern Bloc country, this was an effort met with resistance and harassment from the new authorities. In 1945, the Evangelical Church of the Augsburg Confession with its headquarters in Warsaw was declared the successor of the pre-war Lutheran churches. It gathered believers of Polish and German nationalities. The first head of the post-war church was Rev. Dr Jan Szeruda, who undertook the consolidation of the church within the new state borders. Poland now included the regions of Dolny Śląsk (Lower Silesia) and Mazury (Masuria), where many Protestants lived. However, as a result of the policy of the Stalinist authorities, they were resettled in Germany in the following years. One of the leading bishops during this difficult time was the Rev. Dr Andrzej Wantuła, who went on to serve as Vice-President of The Lutheran World Federation (LWF) from 1963 to 1970.

It was not until modern times that religious life was normalized. After the political transformation of 1989, the 16th-century reformers’ dream of full autonomy and self-determination for Protestants in Poland came true. This happened after the Sejm passed the Act on the Relationship of the State to the Evangelical Church of the Augsburg Confession in 1994.

Today, the Evangelical Church of the Augsburg Confession in Poland (ECACP) is a diaspora church. It numbers over 60,000 believers.